Music (Original Score): Ludwig Göransson – Oppenheimer

The story behind the Oppenheimer flagship track – “Can You Hear the Music” – encapsulates composer Ludwig Göransson’s dedication to his artistic craft. The violin-centric piece employs an astounding 21 tempo changes, which made it nearly impossible to perform in a live orchestra setting. However, Göransson managed to record it in one take by cueing the ensemble with clicks in their headphones corresponding to each tempo change, telling NME that “[w]e spent three days on that one sequence.”

Beyond the most recognizable track, the Oppenheimer score captures the constant crescendoing state of Oppenheimer’s psyche and the particles of an atomic bomb. Göransson seamlessly integrates onscreen elements with musical components, like a crowd’s stomping feet as percussion at the end of “Kitty Comes to Testify,” to amplify the narrative tension.

The late Robbie Robertson’s score for Killers of the Flower Moon also deserves praise. Featuring Osage Nation vocals and a heavy blues influence, the gritty guitar of Robertson’s score responds to very specific changes in the characters’ dynamics. This contrasts with Göransson’s approach to Oppenheimer; apart from the individual trackss “Trinity” (supporting the Trinity test sequence in Los Alamos) and “Can You Hear the Music,” Oppenheimer’s score functions more like a soundscape as many of Hans Zimmer’s latest works now do.

“Can You Hear the Music” has penetrated mainstream culture so deeply that it’s now synonymous with any reference to an obsessive scientific venture. An Original Score Oscar would validate Göransson’s pursuit of perfection and faithfulness, as it did for his Black Panther (2018) score featuring West African talking drums and contemporary hip hop production.

Best Animated Feature Film: Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse

The first Spider-Verse installment in 2018 redefined Western animation, eliciting a shift from the realistic “Pixar look” that dominated the industry for so many years. Across the Spider-Verse pushes the envelope of stylization further, retaining techniques from its predecessor while innovating new ones that contribute to the franchise’s unique look.

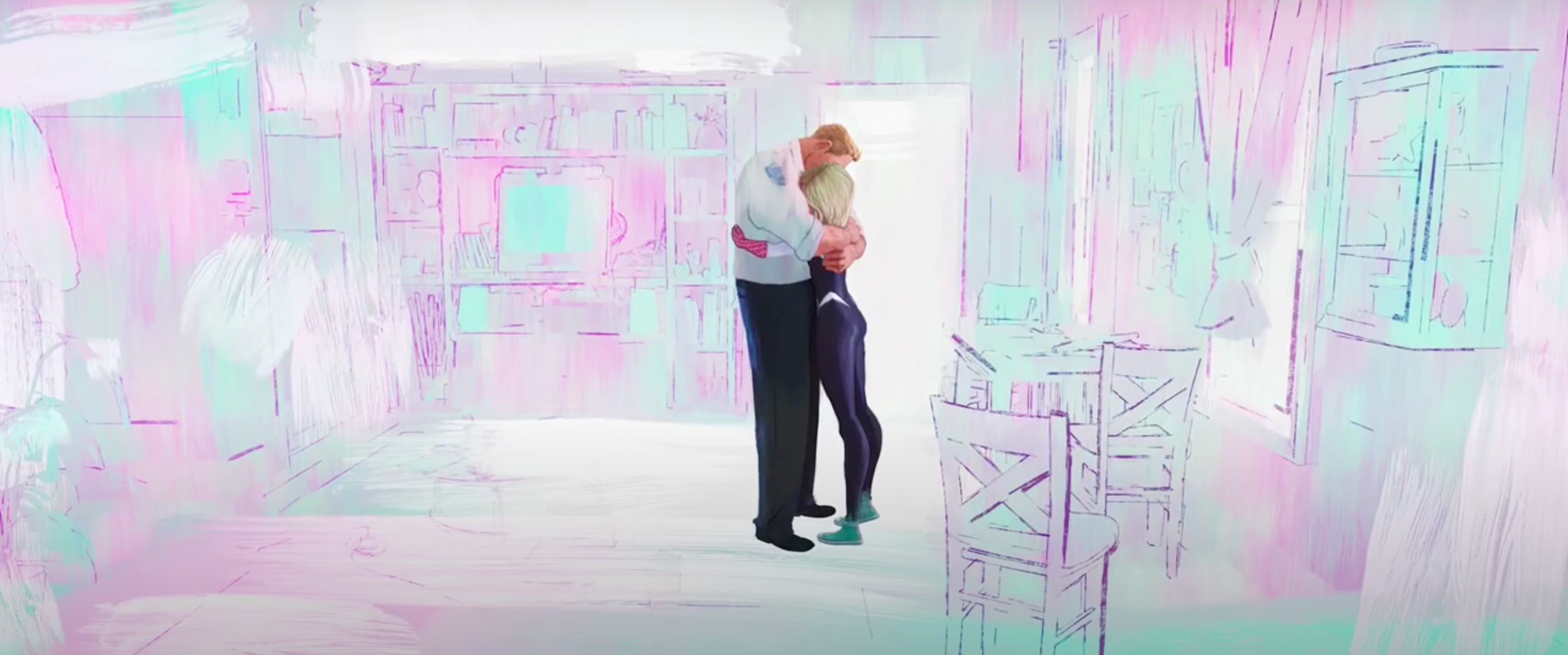

Particularly notable is the chromatic separation between superhero Spider-Gwen and her police officer father as their responsibilities to their respective roles threaten to tear them asunder. The gorgeous pastel hues of the background shift with their competing dynamics, accentuating her emotional isolation. As they reunite as father and daughter and embrace Gwen’s identity as Spider-Gwen, the background also resolves into a neutral palette reminiscent of Gwen’s iridescent pink and blue suit.

The Boy and the Heron also ventures further in its artistic license than any recent Ghibli film. Miyazaki calls upon the visual markers of his previous legendary films, framing this latest installment as an homage to his career as an animator. It’s pleasing and nostalgic but doesn’t offer a cohesive viewing experience, and the lack of a clear storyline detracts further from its clarity.

Given that The Boy and the Heron is reported to be Miyazaki’s final work (yes, really this time!), it’s possible that the Academy will honor him with the 2024 awards as a tribute to his work as a whole. Despite this, Across the Spider-Verse arguably deserves it more for its preservation of artistic cohesion while blending a multiversal number of styles. If the Spider-Verse sequel takes home the Oscar, it’d be the second franchise to win two Animated Feature awards after the perennial category winner Pixar’s Toy Story 3 and Toy Story 4. It’d also be Sony Pictures Animation’s second-ever Oscar after the first Spider-Verse.

Actress in a Leading Role – Lily Gladstone, Killers of the Flower Moon

Lily Gladstone delivers an exceptional performance in Killers of the Flower Moon, an Osage woman who marries a white settler looking to profit from Osage oil. Gladstone portrays an admirable spectrum of emotions, from quiet pride for her Osage identity to raging anguish at the successive deaths of Osage people at the hands of the white settlers. Spending her early years in the Blackfeet reservation in Montana, Gladstone steadily built a career on both theater and film roles while also working with the National Indigenous Women’s Resource Center in teaching violence prevention acting workshops. An Actress Oscar will make her the first Native American to win in the category; she has already won a Golden Globes Best Actress award for the role.

Carey Mulligan also holds an understated yet deep-rooted foundation in the biopic Maestro. Each scene reminds the audience that although the film follows the story of conductor Leonard Bernstein, Mulligan’s Felicia Montealegre is its emotional core as Bernstein’s partner. In one particular scene, the perpetually unfaithful Bernstein slips his hand interlocked into his friend’s while Felicia watches next to him. With only a starkly lit half-profile and dewy eyes, Mulligan conveys it all – shock at Leonard’s boldness, yet also the lack of surprise at her husband’s lack of self-control.

Actor in a Leading Role – Cillian Murphy, Oppenheimer

Jeffrey Wright’s multilayered portrayal of a conflicted writer is a delight to watch unfold in American Fiction. Effectively capturing the awkwardness of a “code-switch” between one’s true self and how others expect one to behave, he feeds off of the nervous performances of his white costars to highlight their sheer absurdity.

Reviews have criticized Cooper’s performance in Maestro as “Oscar-fishing.” Admittedly, his character Leonard Bernstein feels almost hollow in the “Resurrection Symphony” sequence where he conducts the Mahler composition in an expansive cathedral. Cooper swings his baton in a crazed one-man dance with no regard for his appearance as the symphonic orchestra’s combined sound swells around him. However, perhaps therein lies the core of Cooper’s character: he’s a hollow shell of a man trapped by his pursuit of musical perfection and “love for all,” unable to see how it’s eroded his relationships and reputation.

Cillian Murphy is finally given the spotlight in a Nolan film after working with him in several other feature films. Unlike other portrayals of lonely geniuses such as Cumberbatch in The Imitation Game and Eddie Redmayne in The Theory of Everything, Murphy’s emotional range is quite limited in Oppenheimer. The psychological devastation he conveys with his perpetually wide-open eyes, however, is simply unmatched. Despite having never witnessed the war firsthand, Murphy’s eyes are shell shocked by the aftermath of the scientific revolution he birthed.